The Neal Auction Company showroom on Magazine Street sizzled with anticipation Friday afternoon as bidding began on a circa 1840 painting of an enslaved man named Frederick. The auctioneer, Michelle Leckert — who is also the auction house’s president — whacked the palm-sized gavel time and again, as precious objects including vintage Louisiana duck decoys, a classical American footstool, and 19th-century watercolor sketches were snapped up by bidders.

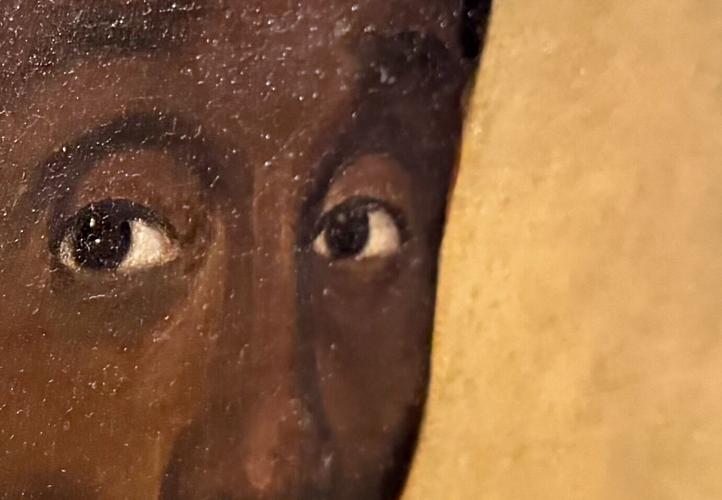

But the rare, pre-Civil War portrait of the formally-dressed Black man that was expected to sell for $300,000 to $500,000 was certainly the centerpiece of the selection. The dozen onlookers in attendance, plus the auction house staff members manning the phones and computers came to attention as the sale began.

Time and again voices cried out “bid” as the price climbed from $275,000 to $425,000, before pausing. With a loud clack, the painting was sold to a telephone bidder. The sale price, plus Neal’s 22 percent commission amounted to more than a half-million dollars.

Immediately, the painting was taken from its spot in a small gallery it had occupied for weeks and spirited to a more secure location. Marney Robinson, the auction company’s director of fine art, explained that once the painting sold, it belonged to the buyer and more robust security protocols kicked in.

Robinson said she could not reveal the identity of the buyer, which could have been either a private collector or institution, but she was confident the painting “will be in excellent hands.” Speaking for the company, she said “we’re very happy” with the sale price, which fell in the center of its estimate.

Once the painting’s new home is known, Robinson said, she hopes that perhaps descendants of Frederick Baker — as he was known late in life — “get to see the painting.”

The 1840 portrait of an enslaved man named Frederick, attributed to C. T. Parker is displayed in its own small gallery at Neal Auction Company

Who was Frederick?

Fredrick’s role in the society of northeastern Louisiana in the era before the Civil War is complicated and somewhat problematic. According to research by historian Katy Morlas Shannon on behalf of Neal Auction, Frederick was born in 1802, probably in Virginia, and became the property of Dr. Rush Nutt, a scientist who relocated to Mississippi in 1815 where he became a cotton planter. Frederick was later inherited by Nutt’s son.

Frederick was, in the brutal parlance of the time, the “slave driver” of the Nutt family’s Louisiana properties, a position valued by his white owners. As revealed by Shannon’s research, Frederick was in charge of lumber processing, drainage, levee building, planting, harvesting as well as agricultural tasks. “In that kind of situation, he would have had to discipline other enslaved people,” she said.

Frederick had a “leadership role and was trusted,” Shannon said, which may explain why he was the subject of the sort of laborious oil portrait usually reserved for aristocrats. Nonetheless, as an enslaved man himself, he would have suffered the inhumanity of the plantation system. There is some evidence, Shannon said, that Frederick was once whipped for correcting a plantation overseer.

“To have survived all that he did,” Shannon said, “he had to be strong, and have a commanding presence. He was incredibly savvy and was walking a fine line.”

At the end of the Civil War in 1865, Frederick was freed. He adopted the surname Baker became a farmer and minister, disappearing from the historic record in 1872. His portrait remained the property of the Nutt family and, until recently, hung in their Natchez, Mississippi mansion known as Longwood.

The 1840 portrait of an enslaved man named Frederick, attributed to C. T. Parker is displayed in its own small gallery at Neal Auction Company

The architecturally splendid Longwood mansion is a Natchez tourist attraction. Dr. Terrel Williams, a member of the executive committee of the Pilgrimage Garden Club that has owned the Longwood mansion and the Frederick portrait since 1970, said the organization decided to sell the painting because, as its value has grown in recent years, it became increasingly difficult to properly protect and insure it.

Money from the sale will go to maintaining Longwood. A Neal representative declined to reveal the percentage the auction house keeps as a commission on the sale.

The appearance of Frederick’s portrait at Neal is its second visit to Uptown New Orleans. In 1884, New Orleans staged the World Cotton Centennial, a Reconstruction-era world’s fair centered in what’s now Audubon Park. Frederick’s portrait was exhibited in the “Colored People’s Exhibition” within the Cotton Centennial, a large exhibit meant to highlight the role of Black people in American culture.

Skip to main content

Skip to main content