Rewind: University of Hyderabad’s Arab Spring moment

For students of University of Hyderabad, the fight to protect Kancha Gachibowli land is more than just a protest; it is a battle for the soul of the city and university, where history, ecology, progress stand at a crossroads

By Dr Akhil Kumar, Dr Anudeep Gujjeti

Hyderabad, a city steeped in 400 years of history, is changing faster than ever. Towering glass structures rise where ancient rocks once stood, roads stretch over what were once serene lakes, and the green canopies that sheltered countless birds and mammals are vanishing. The air hums with construction, the land shifts beneath heavy machines and the quiet spaces of the past fade into memory. But in this battle between progress and preservation, the question remains — what will Hyderabad become when the echoes of nature are replaced by the sounds of a city that never stops building?

In the past few days, the University of Hyderabad (UoH), one of the premier institutions of academic excellence in India, has transformed into a canvas of resistance. Students have taken to the streets, painting their protest in bold, defiant strokes, refusing to let their campus be reduced to yet another casualty of urban expansion. Their fight is against the Telangana government’s plan to auction 400 acres of land in Kancha Gachibowli, once public and green, to private players for a technology park.

Battle for the Soul

Murals of lost landscapes and slogans of defiance adorn the walls. For students, this is more than just a protest; it is a battle for the soul of the city and the university, where history, ecology and progress stand at a crossroads. This thriving biodiversity hotspot, woven into the very fabric of Hyderabad’s natural history, now faces an uncertain future.

Conservationists and civil society groups have raised an urgent alarm on the Revanth Reddy government’s plans to auction the ecologically rich land. When representatives met with Cabinet Ministers, they did not speak of mere statistics and numbers but of the lives at stake, of the seven species protected under Schedule I of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, that call this land their sanctuary.

Photo credit: Raghu Ghanapuram, PhD Scholar (Computer Science), UoH.

The Indian peafowl, with its iridescent plumage that dances in the sunlight; the Bengal monitor lizard, a quiet yet vital predator of the ecosystem; the Indian rock python, coiling within the underbrush; the elusive four-horned antelope, darting through the open spaces; the osprey, soaring over shrinking water bodies; the colour-shifting Indian chameleon, blending into its disappearing surroundings, and the Indian star tortoise, a silent guardian which has long found refuge in the undisturbed patches of Kancha Gachibowli — all stand to lose their home.

More than 15 years ago, between August 2008 and August 2009, researchers from the University of Hyderabad, in collaboration with World Wildlife Fund (WWF)-India’s undivided Andhra Pradesh State Office, led by its State Director Farida Tampal, undertook an extensive ecological survey. The study catalogued a diverse range of species, including various herbs, shrubs, creepers, grasses and trees, as well as butterflies, odonates, arachnids, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals.

Photo credit: Raghu Ghanapuram, PhD Scholar (Computer Science), UoH.

The Vata Foundation, a voluntary organisation led by Uday Krishna, has taken the battle to court. Their petition to the Telangana High Court argues that the land is more than just real estate; it is a sanctuary for countless other species that have coexisted here long before skyscrapers and highways altered the city’s skyline.

The Fight Continues

The students’ fight to preserve the green spaces within their university campus is not a recent development. Time and again, the university has witnessed numerous protests, where both students and faculty have stood together, determined to protect the natural beauty of their campus. They have valiantly resisted attempts to alter the landscape, refusing to let progress come at the cost of ecology. Their struggle is not just about saving trees and open spaces, it is about safeguarding the very essence of their academic sanctuary.

During the tenure of former Vice-Chancellor Professor Seyed Hasnain, the university found itself embroiled in a fierce battle between administration and faculty members, students. The administration’s decision to allocate 200 acres of land to the Care Foundation for the establishment of a medical college sparked widespread opposition. Students and faculty saw this as a direct threat to the university’s ecological landscape and academic integrity. Protests erupted across the campus. For many, this was not just a fight to save land but a stand against the creeping commercialisation of their institution.

The resistance did not end there. In 2010, the university faced further backlash over its plan to establish a Knowledge and Innovation Park (KIP). Amid mounting pressure, the UoH was forced to shelve the project, but concerns among faculty members remained high. They openly criticised the administration for prioritising commercial ventures over the university’s core mission of education and research.

These struggles became defining moments in the university’s history, a testament to a community determined to protect its intellectual and environmental heritage against the forces of unchecked expansion, says Professor Satya Prakash, a faculty member.

Mushrooming Movement

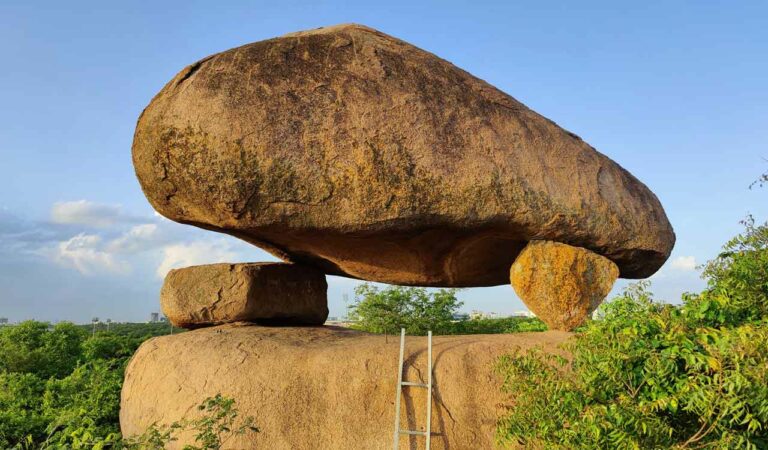

Hyderabad’s landscape is defined not just by its lakes and heritage structures but also by its unique rock formations as silent witnesses to the city’s ever-changing skyline. Among these, the iconic Mushroom Rock, nestled within the contested 400-acre land in the university, has become more than just a geological wonder. It has transformed into a symbol of resistance.

As protests erupted against the government’s decision to auction this ecologically rich land, Mushroom Rock emerged as the face of the movement—a steadfast, immovable force standing against the tide of urban expansion. Students gathered under its shadow, raising banners and voices in unison, vowing to protect what remains of Hyderabad’s natural heritage.

The ancient rocks of Hyderabad are more than just silent monoliths; they cradle life within their crevices, offering shelter to countless birds, reptiles and insects. The erstwhile Andhra Pradesh government under Chandrababu Naidu took a pioneering step by including these natural wonders under Regulation No. 13 of the Hyderabad Urban Development Authority (HUDA), ensuring their protection alongside heritage buildings and precincts. This made Hyderabad the only city in India where rocks are legally safeguarded as part of its natural heritage. However, even after being replaced with the Heritage Act, it has failed to safeguard the natural wonders.

Sangeeta Varma, Vice President of the Society to Save Rocks, says the rocks of Hyderabad are nearly 2.5 billion years old, shaped over millennia by the relentless forces of nature such as rain, wind and sun, gradually chiselling solidified magma into the magnificent formations seen today. Their immense geological and ecological value makes them irreplaceable.

Adding further, she says, clearing the spaces around these ancient formations could exacerbate Hyderabad’s already pressing water crisis. These rocky landscapes play a crucial role in groundwater retention and ecological balance, and their destruction may lead to even more severe water shortages in the future and much faster loss of related flora and fauna.

Hidden Sanctuaries

Beyond Mushroom Rock, there are other hidden sanctuaries such as Buffalo Lake, High Rocks, Virgin Rocks and Peacock Lake. “There is no answer from the government on where these species and trees will be relocated,” fumes a Nallagandla resident, Digvijay Chauhan, who lives near the university.

Photo credit: Raghu Ghanapuram, PhD Scholar (Computer Science), UoH.

Hyderabad has always been a city of resilience, where the voices of its people rise in unison to protect what they hold dear. From the towering banyans of Chevella to the untouched wilderness of Damagundam forests, and now to the battle for the green heart of the University of Hyderabad, its citizens have always taken a stand to protect its natural heritage.

Arab Spring Revisited?

Across the world, students have long stood at the forefront of revolutions, infusing movements with fresh energy and innovative tactics — from the Arab Spring, where youth-led digital mobilisation challenged authoritarian regimes, to global climate strikes inspired by schoolchildren.

In India, from the Save Aarey Forest campaign in Mumbai to grassroots movements to preserve sacred groves, indigenous forests in the Northeast to Goa’s Mollem forest, students have mobilised support through platforms like Instagram, X and YouTube. By creating visually compelling content, collaborating with eco-conscious influencers, and using hashtags to trend causes, they have transformed local environmental issues into national conversations. They were connected with the digital world through documentary-style posts and collaborations with climate storytellers.

UoH students, through Instagram stories and reels, have showcased real-time protests, while X threads provided them quick, shareable facts and calls to action, online petitions and mails to officials, including the Prime Minister’s Office, gained momentum through student-led awareness drives, often going viral. These digital strategies not only drew attention from the public but also put pressure on policymakers.

With their peaceful on-field protests, tech-savviness and commitment to the environment, students have proven that activism in the digital age can transcend boundaries through an integrated approach by turning clicks into change for the planet.

As yet another piece of their cherished landscape faces the threat of concrete and steel, the spirit of the University of Hyderabad remains unshaken. For them, saving a tree is saving a story, and protecting the land is protecting a legacy.

Musings of Mushroom Rock

Long before the digital age, when there were no smartphones or social media to capture moments, Mushroom Rock was the place where time slowed down. Students would escape there after long lectures, seeking solace in its shade or finding inspiration in its rugged beauty.

For alumni, the Mushroom Rock is not just a relic of the past but a living memory, an enduring piece of their youth that connects them to a simpler, more magical time, says Uma Magal, a UoH alumna and film producer-director.

Photo credit: Raghu Ghanapuram, PhD Scholar (Computer Science), UoH.

Every university alumnus carries a piece of nostalgia, a photo of Mushroom Rock tucked in their album, a timeless memory on their phone. It was a landmark of youthful romance; many love stories found their beginnings there, whispered in the evening breeze.

One such story belongs to renowned Telugu filmmaker Mohan Krishna Indraganti, who once stood beneath its grand arch and asked the most important question of his life—proposing to his future wife in the very heart of the university’s natural sanctuary.

“The timeless song E Nallani Rallu sung by Ghantasala in Amara Silipi Jakkana celebrates the enduring strength and artistry of black rocks, much like the ancient granite formations of Hyderabad that have withstood the test of time”

Uma Magal,

UoH alumna who produced and directed Other Kohinoors: The Rocks of Hyderabad, which was screened at various national and international film festivals

The seven species protected under Schedule I of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, that consider Kancha Gachibowli land their sanctuary:

- Indian peafowl

- Bengal monitor lizard

- Indian rock python

- Four-horned antelope

- Osprey

- Indian chameleon

- Indian star tortoise

A world unlike any

Hidden within the rugged grasslands of Kancha Gachibowli lies a world unlike any other, a delicate ecosystem home to species found nowhere else on Earth. Among them is Murricia hyderabadensis, a rare spider discovered only in 2010, its existence tied entirely to this land. The grasslands here are also the last refuge of the Indian roller, Telangana’s State bird, known as Palapitta in Telugu, a sight considered auspicious on Dasara. Its vibrant blue wings have graced this landscape for centuries, a symbol of fortune and tradition.

The tree diversity in this area also includes marking nut, and in Telugu it is known as Chakkali Jeedi (Washerman’s Nut), an essential resource for the washermen community. An ecological heritage report by environmentalist Arun Vasireddy mentions that if these trees are gone, history and culture will be erased.

(The authors are alumni of the University of Hyderabad)

Related News

-

Telangana: Woman kills infant daughter, hangs self to death in Peddapalli

4 mins ago -

RGV announces horror-comedy ‘Police Station Mein Bhoot’ with this star

36 mins ago -

TGRERA freezes bank accounts of Realtor for not completing apartment complex in Bachupally

37 mins ago -

Aparna Serenity apartment owner restrained from making alterations by TGRERA

2 hours ago -

Allu Arjun starrer AA22’s first look poster sparks plagiarism row online

2 hours ago -

Horoscope: Check out your astrological predictions for April 10, 2025

3 hours ago -

RCB vs Delhi Capitals: Face-off between two gritty sides of this season

9 hours ago -

BRS leaders Krishank, Dileep Konatham grilled for nine hours in UoH case at Gachibowli police station

9 hours ago