Five Years Later: How COVID Triggered a School Choice Renaissance

Dissatisfaction with schools, and a supercharged conservative movement, allowed ESAs to take a leap since the pandemic.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

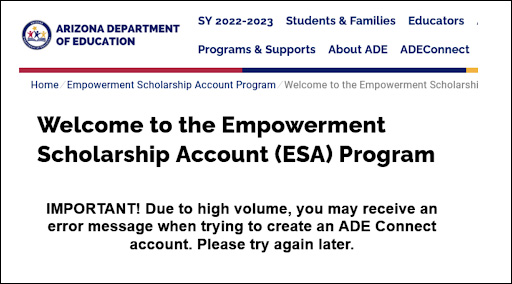

In August 2022, visitors to the Arizona Department of Education webpage were greeted by an unusual message: Due to a “high volume” of users, the note read, they might have trouble applying to participate in the state’s Empowerment Scholarship Account program.

It was the second such IT mishap of the year, following an episode in which a crush of parents temporarily overwhelmed the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction’s site that winter. Libertarian activist Corey DeAngelis, then rising to fame as an arch critic of teachers’ unions and Democratic politicians, said the trend convinced him that the experience of virtual learning had ignited in families a desperate hunger for more educational options.

“I’d been chugging away at this before COVID, but it really took off when we were getting into debates about reopening schools,” he recalled.

Five years after the onset of the pandemic, DeAngelis is one of the leading voices in an education world turned upside down by its effects. After a generation at the center of both federal and state policy, bipartisan reforms like charter schools and test-based accountability have receded from the spotlight; at the same time, billions of dollars were devoted to private initiatives that previously won few headlines and scant financial support.

Since 2020, over 20 states have either enacted or expanded some form of private school choice, and 13 extend eligibility to all families within their borders. Over 1 million children now access those offerings, according to the advocacy group EdChoice, and over 20 million are eligible to do so. And just since the beginning of 2025, nearly 100 bills have been filed that would push the needle further, potentially allowing even more resources and greater flexibility for families in states like Texas, Florida, and Ohio.

Patrick Wolf, a political scientist at the University of Arkansas who has studied voucher-like systems for decades, contrasted their fast spread over the last few years with the halting progress seen in the 2000s and 2010s. In particular, he said, education savings accounts (ESAs) stand out as having “found their moment.”

“It’s been amazing to see from a movement that had kind of plateaued and seemed stagnant just prior to COVID,” remarked Wolf, who has energetically argued for the benefits of choice. “Now it’s dynamic like crazy, with all kinds of variations and evolutions that we didn’t anticipate even six or seven years ago.”

When we leaned too heavily on lefty messaging on school choice, it didn't do much to convince Democrats to come along. But it might have alienated some of the more conservative or even moderate Republicans.

Corey DeAngelis, private school choice activist

The leap forward was made possible by a pronounced shift in perceptions of schools, especially among Republicans. The structure of the ESA, a lightly regulated grant placed directly in the hands of parents, proved both politically attractive and legally viable in ways that earlier voucher schemes were not. Spurred by competitive pressures among red-state lawmakers — and accelerated by a political strategy relying on Republican legislative majorities, rather than the assent of voters — the new benefits took hold quickly.

No less pivotal was the adoption of school choice as what DeAngelis called a “litmus test issue” for conservatives, who proved comfortable jettisoning Republican legislators standing in their way. Household names on the right, including Donald Trump and Betsy DeVos, have personally intervened in state-level fights, while figures like Christopher Rufo national profiles by directly confronting social controversies in the classroom. The resulting fights have often taken a vituperative tone uncommon to discussions of K–12 schools.

Jon Valant, director of the Brown Center on Education Policy at the left-leaning Brookings Institution, said he believed school choice proponents had broken through by yoking their vision of an open education marketplace to the ascent of culture warriors like Rufo and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis.

“Those two groups came together in a marriage of convenience, and you saw the push for ESAs ride the wave of frustration that was building,” Valant said. “That frustration became political fuel in a lot of red states.”

A gaping ideological divide

Accounts differ on the extent of public anger arising from the long era of school closures, quarantines, and mask mandates. But for many, COVID led to a serious reappraisal of the state of public education.

It’s been amazing to see from a movement that had kind of plateaued and seemed stagnant just prior to COVID. Now it's dynamic like crazy.

Patrick Wolf, University of Arkansas

According to the polling organization Gallup, 70 percent of parents said they were either completely or somewhat satisfied with the education their kids received in 2024 — down 10 points over the past two years, but still well above the figure for Americans as a whole. Among that larger group, the proportion dissatisfied with the quality of American education crested at 63 percent in 2023 and remained at 55 percent last year, compared with just 43 percent of survey respondents who said they were satisfied.

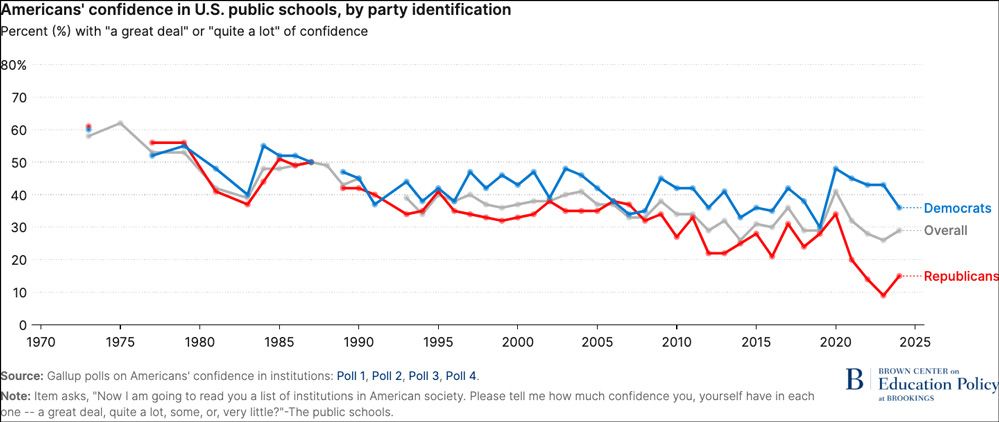

Beneath the overall numbers is a gaping ideological divide. Virtually identical numbers of Democrats and Republicans said they had “a great deal” or “quite a bit” of confidence in U.S. schools in 2019 (30 percent of Democrats vs. 28 percent of Republicans), but a pandemic-era divergence exploded the very next year. By 2023, 43 percent of Democrats said they were mostly confident in schools; an extraordinary 9 percent of Republicans agreed.

What’s more, even while families approved of the performance of their local schools, the impact of the pandemic led thousands to pull their children out of them.

A 2021 study by Stanford economist Thomas Dee found that traditional public institutions lost 1.1 million students in the fall of 2020, largely driven by a substantial departure of kindergarteners and elementary schoolers. The decline was 40 percent higher in districts that provided only remote instruction at the beginning of that academic year. A separate analysis from the conservative American Enterprise Institute found larger, more sustained enrollment drops between 2020 and 2022 in districts that kept schools closed longer and enforced mask mandates when students returned to campus.

Martin Lueken, a researcher at EdChoice, said that prolonged closures both revealed and amplified the existing demand for private school alternatives. Although the process of building momentum for private choice initiatives was “slow” in the years before the pandemic, he added, the massive disruptions to school routines acted as a powerful accelerant.

“There has always been a recognition that in order for these programs to be implemented, you need to build a broad constituency for them,” Lueken said. “You never want to let a crisis go to waste, and COVID really shrunk the timeline for this to happen.”

A matter of branding

As parents became increasingly willing to leave their traditional school systems, politicians were converging on a vehicle to facilitate their exit: the education savings account.

ESAs were first introduced in Arizona in 2011 as a resource for parents of students with disabilities. The scope of the proposal was limited, with only 17,000 children eligible to participate in the first year. Compared with other K–12 reforms being pursued in the Obama era, from teacher accountability to rapid charter school expansion, ESAs received little national attention; but school choice advocates hailed their passage, immediately recognizing them as “the way of the future.”

Their early excitement was a reaction to an unprecedented political opportunity— and grounded in two factors that made the policy more likely to gain traction than other forms of private school choice.

The first was legal. An earlier school voucher law had been passed by the Arizona legislature in 2006, only to be swept aside a few years later by state courts arguing that the program violated state law by sending state funds to private or parochial schools. Thirty-seven states have written such prohibitions, known as “Blaine amendments,” into their constitutions since the 19th century.

By contrast, ESAs indirectly facilitate choice by providing families with money and allowing them to use it as they see fit. Supporters in Phoenix quickly grasped the significance of that distinction, moving to expand the accounts to children attending failing schools just a year after they were first enacted.

The second advantage of ESAs was political. Surveys have often shown high levels of support for private school choice, but voucher programs failed at the election booth for decades. Between 1978 and 2007, six states conducted nine different referendum campaigns to determine whether to establish either voucher programs or tax credits for private school tuition. Voters rejected each ballot measure, often by overwhelming margins.

Valant called the branding of voucher programs “toxic,” especially relative to the simple appeal of sending money directly to parents.

“People don’t like ‘private school vouchers,’” he said. “But they don’t really know what an ESA is until they actually dig into the policy details, so they don’t have the immediate baggage that vouchers come with.”

EdChoice’s own tracking survey, conducted with the nonpartisan research firm Morning Consult, consistently showed that about two-thirds of parents had positive attitudes toward ESAs during the pandemic. Even more importantly, Republicans were eager to pass them through the normal legislative process, without risking lengthy and expensive referendum battles.

Since 2021, over a dozen states have passed ESA legislation, significantly increasing the number of American families eligible to receive the accounts. Crucially, most have opted to follow Arizona’s lead by structuring their programs not as targeted benefits for disadvantaged students, but as universal entitlements that gain rapid acceptance among families from all walks of life.

Dan Lips, a senior fellow at the Foundation for American Innovation and veteran education policy analyst, first proposed a regime of ESAs 20 years ago, while working at Arizona’s conservative Goldwater Institute. Reflecting on the decades-long path trod by the school choice community, he called the triumph of the policy a “silver lining” to the damage wreaked by COVID.

Inline pullquote: https://www.brookings.edu/people/jon-valant/

People don't like 'private school vouchers.’ But they don't really know what an ESA is.

Jon Valant, Brookings Institution

“There’s been an advocacy effort, going back 30 years, to mobilize parents, to fund scholarship organizations, to educate policy makers about the benefits of these types of programs,” Lips said. “I don’t think the strategy changed during the pandemic, we just found a lot more motivated lawmakers who’d had enough with public school systems.”

‘Anti-woke’

Republicans were motivated by more than the urgency of the pandemic, however. During the Biden era, backing for the expansion of school choice became something of a crusade on the right.

For more than half a century, conservatives have favored the evolution of new school models and options outside the public sector. But during the era of bipartisan education reform stretching across the Bush and Obama presidencies, most of that energy was redirected toward the spread of charter schools, a compromise position that also enjoyed the blessing of Democrats leery of any move toward vouchers.

Arguments for direct subsidies of private schools — occasionally drafted into congressional legislation that went nowhere — were usually couched in the language of equity, with a heavy focus on targeting benefits at low-income families and freeing students from underperforming local school districts. DeAngelis said that while those discussions were tailored to win over the left, they tended to backfire.

“When we leaned too heavily on lefty messaging on school choice, it didn’t do much to convince Democrats to come along,” he said. “But it might have alienated some of the more conservative or even moderate Republicans, because they didn’t feel like it was a Republican issue.”

With the arrival of COVID and the presidency of Donald Trump, messaging around the issue changed. Conservative activists and politicians increasingly voiced disapproval of what they perceived as political indoctrination in schools, militating instead for parents to be provided the autonomy to select among institutions more in line with their values. The moment presented an opportunity, proponents argued, to take advantage of the culture war.

One of the most dedicated “anti-woke” combatants of the Biden era was Gov. Ron DeSantis, who pushed Florida’s Republican legislature to adopt strict new rules constraining how teachers can speak about sexuality or other controversial subjects in the classroom. At the same time, he transformed the state into America’s biggest marketplace for school choice, pointedly linking the expansion of ESAs with parents’ desire to escape “woke” instruction.

A similar dynamic is playing out in Texas, now at the precipice of adopting the policy. Republican Gov. Greg Abbott spent the past several years stumping for his favored ESA legislation at a host of Christian (and predominantly Protestant) schools, warning of progressive bias in small towns as well as blue-trending cities. He also moved relentlessly against a contingent of mostly rural Republican legislators who opposed him, succeeding in ousting over a dozen through competitive primaries; revealingly, while those campaigns were crucial to Abbott’s legislative strategy, their messaging focused much less on schools than on the hot-button issue of border security.

Republican donors like former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos got in on the action, spending millions to promote legislation and fund primary challenges against rural GOP legislators who resisted the new laws. In Iowa, where a universal ESA bill was being held up, the chairman of the House education committee was defeated after his opponent was endorsed by the Gov. Kim Reynolds. The bill was passed shortly thereafter.

Conservative media figures have been no less confrontational, casting their adversaries as would-be propagandists seeking to control other people’s children. DeAngelis, whose recent book received praise from President Trump, has proven adept at the cut-and-thrust of social media trolling, personally attacking top Democrats for sending their own children to private schools while rejecting school choice for others. The popular Twitter account Libs of TikTok takes aim at more targets in the classroom, often circulating videos of teachers its creator, Chaya Raichik deems ideological or manipulative.

Joshua Cowen, a professor at Michigan State University who fiercely opposes the wave of new laws, said that while school choice has historically been understood as a reform grounded in markets and accountability, it is now principally a means by which the conservative movement can reward sympathetic constituencies and achieve its cultural aims.

“At the end of the day, the real energy for this is the culture war,” Cowen said. “It’s linked to the same energy that rolled back Roe, and…at the same time we’re talking about vouchers expanding across the country, we’re also talking about bathrooms and locker rooms and book bans.”

The future of choice

No one would have predicted that the last five years would be the most tumultuous in the modern history of school choice. Few would hazard a guess at what the next five might look like.

Going forward, it may be challenging even to learn how new ESA systems are affecting student learning. In part, this is because the state statutes passed since 2020 generally have not required private schools to take part in state testing, which could allow lawmakers and researchers to compare the performance of pupils in the private and public sectors against one another.

The University of Arkansas’s Wolf, who has previously conducted longitudinal studies of voucher programs in Washington, D.C., Milwaukee, and Louisiana, said he believed scholars could still devise strategies to identify the benefits or demerits of new private school programs even in the absence of testing — many already emphasize later-life outcomes such as college enrollment and completion — but added that he expected to face some obstacles.

“There’s more of a sense that, ‘We want to do this, and we’re confident that it’s going to be good for families,’” Wolf observed. “When states have that attitude, they’re somewhat less enthusiastic about bringing a scholar in to actually kick the tires and determine if their expectations are correct.”

The real energy for this is the culture war. At the same time we're talking about vouchers expanding across the country, we're also talking about bathrooms and locker rooms and book bans.

Joshua Cowen, Michigan State University

It is also difficult to project the future progress of the ESA wave. A large number of states with Republican governors and legislatures have already taken action, leaving mostly purple and blue states without some form of private school choice. Few Democrats have been willing to touch the idea; Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro, a rising star in his party, mused about joining with Republicans to create a voucher offering in 2022, only to back off after a storm of criticism.

Resistance within states, even including those that have passed ESA bills, makes their future difficult to project. The South Carolina Supreme Court ruled last fall that the newly adopted Education Scholarship Trust Funds violated the state constitution, leading to a scramble this year to craft a program that might pass legal muster. And in Arizona, home to the first-ever ESA law, Democratic Gov. Katie Hobbs has made repeated attempts to pare back the accounts, claiming that their growing popularity poses a danger to the state’s finances.

A national, ESA-type entitlement remains the dream for school choice proponents, including the America First Policy Institute, the think tank most closely tied to the Trump administration and its education secretary, Linda McMahon, who previously served as the Institute’s chairwoman. Legislation to that effect has been proposed in Congress, though it would likely have to pass through the budget reconciliation process, which is not ideally suited for the creation of new programs.

Valant said that, once the remaining red states decide on whether to embrace the policy, the U.S. could feature a striking regional contrast in education policy. Democratic- and Republican-leaning states increasingly exhibit a high level of difference on policies like charter school growth, school evaluations, and the science of reading, and ESAs may simply make the contrast more stark.

“For the short term and maybe the intermediate term, we’re going to be in the unfamiliar place of having very different systems of education governance in red states and blue states. That just isn’t what we’ve done in the past.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)