Loading your audio article

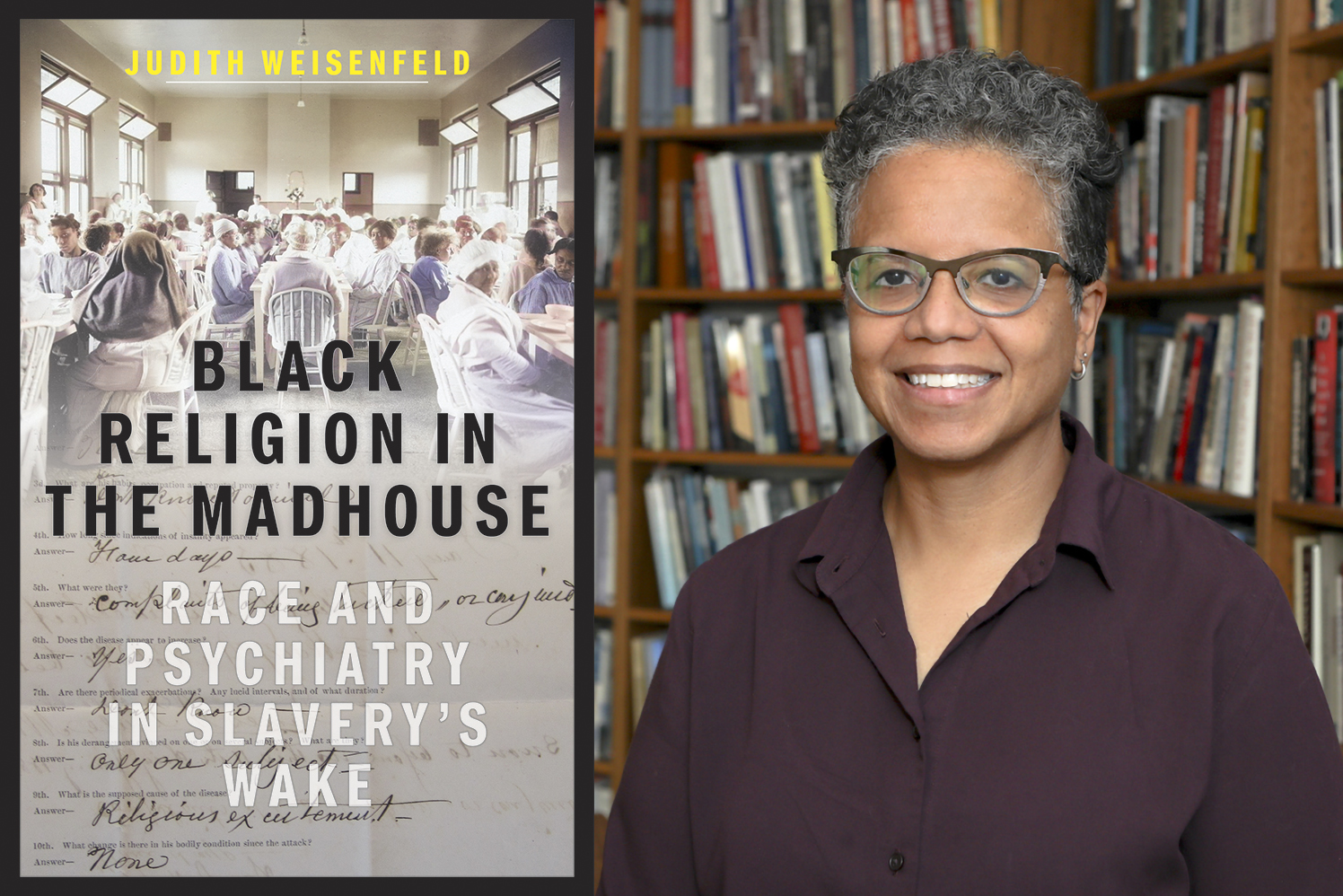

(RNS) — Princeton University scholar Judith Weisenfeld has long studied the role of religion and race in America — but it wasn’t until recently that she discovered their historical and troubling intersection with psychiatry.

Her new book, “Black Religion in the Madhouse: Race and Psychiatry in Slavery’s Wake” declares this finding: “there was no other group in American mental hospitals in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries for which attribution of mental illnesses to religious causes was as prominent as for African Americans.”

Weisenfeld, 59, acknowledges how challenging it was to read the range of literature she researched for the book — including psychiatric studies, hospital and court records, and newspaper stories — but she remained determined to reveal the stories of individual patients who lived, labored and sometimes died in institutions after their behavior was labeled as superstitious and overly emotional.

“It was difficult to read this profoundly racist psychiatric theory in the 19th century, to see how it was mobilized in the aftermath of the horrific institution of slavery with the aim, really, of continuing some of the same structures, of capturing Black people in labor, in subordinated social positions,” she said in an interview, “lending the authority of medicine to pathologize one of the central sources of community and connection and ability to survive.”

Weisenfeld, who has no religious affiliation, talked with RNS about how psychiatrists of different races viewed evaluations of Black people near the turn of the 19th century and how Black religious leaders responded then and now to mental health concerns.

RELATED: Therapist, former pro-athlete is bringing mental health conversation to churches

The interview was edited for length and clarity.

Your book includes details about Black people committed to state mental hospitals. What strikes you most about their treatment related to their religion and their race?

The white authorities, both judges and psychiatrists, through the commitment process, brought these ideas about African American religion as a mentally disordering factor. That is what struck me most, the evaluation of individual patients through a frame about race traits and innate racial predispositions regarding religion rather than the engagement of them as individuals.

“Religious excitement” was often cited in reports about the Black Americans treated in these institutions. Could you summarize that broad term and how it was applied to them?

In late 19th century and into maybe the first decade of the 20th century, the main diagnostic categories for mental illness were mania — so, an excitement — and melancholy, sadness, and white psychiatrists focused primarily on mania. There’s an argument that many of them make that “the Negro” is naturally happy-go-lucky, and so, not prone to melancholy. So, they’re focusing on mania, kind of agitation or excitement. And one of the causes that is frequently put forward for acute mania or chronic mania is religious excitement. It becomes associated with Blackness by the end of the 19th century to a greater degree than it had been before. It’s still applied to white patients, but not as much.

A postcard from 1885 of Central State Hospital in Peterburg, Va. (Courtesy image)

You note that white psychiatrists who treated Black patients often were religious people themselves. How do you think their perspective on faith influenced how they treated the African Americans in their care?

I found two things characterized a lot of the early white psychiatrists, who were the first group to begin to treat Black patients in these hospitals in large numbers after the end of slavery. One, that many of them had been enslavers or from enslaving families, had fought in the Confederacy, so they had commitments to slavery and a certain kind of post-slavery order. And the other is that they were, many of them, quite involved in Protestant denominations. They were Baptist, Methodist, Episcopal, Presbyterian. I could find them as representatives to state denominational conventions. It seemed to me important that I not understand this as a story that was about a secular science versus the religious worlds of African Americans in the late 19th and early 20th century, but as a work they were doing that was in part about naming what is good religion. They are at once describing their own world, by implication, as good and useful and beneficial, morally and mentally, physically, and pathologizing African American religious practices.

How did Black religious leaders respond to religious excitement being featured increasingly in these diagnoses of insanity among African Americans in the late 1800s and the early 1900s?

Black religious leaders have their own worries about the public impression of African American religious practice as excessively embodied or overly emotional. They see it as something that is potentially unrespectable and potentially damaging to claims for civil rights in this period. Independently of the medical frame, there are Black church leaders like Daniel Alexander Payne, who’s a bishop in the AME Church, arguing we have to get control of these primitive practices like the ring shout and the revival, because now we need to have an educated ministry and respectable worship. But they also absolutely resist the idea that these are pathological manifestations of African American religion.

The dining hall for African American patients at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, D.C., circa 1915. (Photo courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration/Creative Commons)

Are there a couple of examples of what was meant by religious excitement?

It’s an umbrella term. In the 19th century, they’re focused on this idea that Black people are innately superstitious, and in this way, they are looking at practices that have their origins in West and West Central Africa, that come under the heading of conjure or hoodoo, for example. If you saw Ryan Coogler’s (movie) “Sinners” recently, you saw hoodoo and rootwork and conjure happening there. These practices are often named by Black patients, actually, as something that has caused their mental distress. They’ll say “I’m upset or agitated in this way because somebody conjured me. Somebody did this to me.” And in that sense, they don’t need a psychiatrist. They need somebody to reverse the conjure, someone who knows hoodoo. But the medical establishment frames this as superstition and mental illness.

And then they highlight what they talk about as an innate emotionalism: Black religion is emotional and not rational. It can be revivalism, the embodied practices. And then when Holiness theology comes into the frame and Pentecostalism in the early 20th century, and people are speaking in tongues and experiencing baptism of the Holy Spirit, that’s what gets framed as pathological under religious excitement.

How did early Black psychiatrists and social scientists change views of religion, race and psychiatry?

They begin to step forward and present a new kind of psychiatric literature that considers social context, economic stress, lack of educational opportunities, racism, as the cause of mental illness, rather than something like religious excitement.

Did you find this work mostly disheartening, and if so, what drove you to continue?

Mostly disheartening, yes. To just read the patient files of individuals, many of whom spent many, many years in those institutions and died there, that was hard.

So, the arc, in a way, is a hopeful one, in that we get to these newer movements, where people are trying to reshape the theory and practice. And I wanted to give people resources to think about what the legacies might be for religious leaders and for medical professionals, and perhaps even police authorities and courts, to think about where they might be mobilizing some of these assumptions that are in the afterlives of this story that really starts in a profound way in the late 19th century.

RELATED: Judith Weisenfeld, “Anti-Racism as a Spiritual Practice”

Arabic

Arabic Chinese (Simplified)

Chinese (Simplified) Dutch

Dutch English

English French

French German

German Italian

Italian Portuguese

Portuguese Russian

Russian Spanish

Spanish