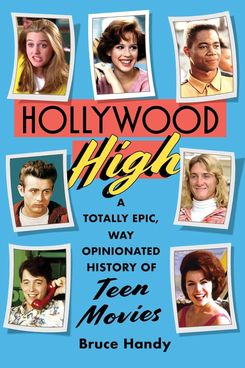

One of the pleasures I found in researching and writing Hollywood High: A Totally Epic, Way Opinionated History of Teen Movies, which is out today, was the way the films reflect their eras yet can also be in dialogue with one another, even across decades and generations. I found all kinds of interesting through-lines: cars, clothes, cliques, school, the threat of impending adulthood.

And, of course, sex. The teen-movie genre begins with Andy Hardy, the archetypal high-schooler played by Mickey Rooney in a series of family films produced from 1937 until 1946. Andy (like Mickey) was unabashedly horny, though the era’s restrictive Production Code wouldn’t have countenanced that exact term. His studio, MGM, kept his impulses in check by treating them as a running gag. In Judge Hardy’s Children, for instance, he confesses to his father, the titular judge, “I want to kiss all the pretty girls. Do you think I’m normal?” Stifling a laugh, dad offers reassurance: “Well, yes, Andy, I really believe you are.” Cue warm chuckles from the adults in the audience.

Two decades later, in 1959’s Gidget, Sandra Dee’s title character is eager to take “the step” and do more than just kiss, but she’s still willing to confide in a parent. “Aw, Mom, I could perish!” she wails. “Last night, after all these hours of concerted effort, I still come home as pure as the driven snow.” Surprisingly, given most people’s assumptions about the uptightness of the 1950s, Mom is not alarmed. Rather, like Judge Hardy before her, she’s inwardly amused but empathetic, allowing that “a girl does have to become a woman” eventually, but then offering a bromide about true womanhood having more to do with bringing out “the best” in a man than just mere sex. Topic A is once again acknowledged but diffused.

Jump ahead to 1982 and the release of Fast Times at Ridgemont High. No one is consulting parents in that film. In fact, parents are not even referenced or depicted, aside from one brief glimpse of a mom just before Jennifer Jason Leigh’s Stacy sneaks out at night to lose her virginity to an older guy she met at the mall. Stacy has only consulted her friend Linda (Phoebe Cates), who urges, “What are you waiting for? You’re 15 years old. I did it when I was 13. It’s not a huge thing. It’s just sex.” When Stacy voices disappointment about the act — it takes place in a graffiti-covered Little League dugout, one of the loneliest sex scenes ever filmed — and regret about being ghosted, Linda offers more wisdom: “What’s the matter? He’s a stereo salesman. You want to marry him?”

Fast Times at Ridgemont High was based on the nonfiction book of the same name written by Cameron Crowe, who spent the 1979–80 school year posing as a student at a Southern California high school. I myself was class of ’76, and the faux knowingness about sex depicted in the book and film very much jibes with my own teenage memories. We tried so desperately hard to be casual about it. (And I, for one, would have died before I ever discussed sex, love, or anything in the vicinity with my parents.)

But of course, contra Linda, sex is very much a huge thing. And in the digital era, it’s only become more omnipresent in kids’ lives, so much so that its negation would become very much the point of one of the biggest teen-movie franchises ever.

Excerpt from 'Hollywood High: A Totally Epic, Way Opinionated History of Teen Movies'

“We’ve all had the experience of being [teenagers] and feeling everything is life and death. You know, ‘I have nothing to wear today, I’m going to kill myself.’ What’s wonderful about this story is that everything actually is life and death.” —Melissa Rosenberg, screenwriter of all five Twilight movies

Writing in Time in 2009 — following the releases of Twilight the bestselling book, in 2005, and Twilight the blockbuster movie, in 2008, when the giddy crowds who packed novelist Stephenie Meyer’s book signings had metastasized into screaming mobs who went bonkers whenever the stars Kristen Stewart and Robert Pattinson were trotted out on a stage or red carpet — the author Lev Grossman offered an astute take on the story’s appeal:

Beatlemania is the comparison that everybody makes, but Twilight is more like the Beatles in reverse. Beatlemania was a reaction to the buttoned-down, sexually repressed pop culture of the 1950s. Twilight is a reaction to the reaction — it’s a retreat from the hedonistic hookup culture that the sexual revolution begot. Nobody hooks up in Twilight. Meyer put sex back underground, transmuted it back into yearning, where it became, paradoxically, exponentially more powerful.

Powerful enough that the four main Twilight novels have sold more than 160 million copies worldwide; the five films made from those novels have taken in more than $3 billion at the global box office.

Appropriately, the Twilight Saga (the franchise’s official descriptor) began with a dream. Meyer, the dreamer, was then a twenty-nine-year-old housewife living in Phoenix, raising three sons with her husband, an auditor at an accounting firm. “In my dream,” she later recounted, “I can see a young woman in the embrace of a very handsome young man, in a beautiful meadow surrounded by a forest.” Essentially, she was dreaming up the generic cover for a generic romance novel. But there was a twist: “Somehow I know he is a vampire.”

Meyer wasn’t yet a novelist, or any kind of writer, but “for fun” she jotted down the scene. “When I got done I was so interested in the characters that I wanted to see what would happen to them next. And so, I just wrote and let whatever happened to them happen.” Once enough things had happened, she went back, found a starting point, and wrote forward to the midpoint meadow scene. Within three months, she had a five-hundred-or-so-page manuscript, and less fecund novelists reading this must surely be weeping.

The result was Twilight, the story of a normal seventeen-year-old girl and the 103-year-old immortal who loves both her and her blood type. The publisher, Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, knew it had a commercial property on its hands, but nevertheless underestimated the appeal. Twilight was published in October 2005, with an initial printing of 75,000 copies — an ambitious though not outrageous run. A slow-burn success, the book sold well enough that the second volume, New Moon, received a first printing of 100,000 when it was released eleven months later.

By the time Eclipse was published in August 2007, the series had acquired an obsessive fandom big enough to nip at the heels of those devoted to Harry Potter or Star Wars. The finale, Breaking Dawn, was greeted on August 2, 2008, with Potter-style midnight release parties, a print run of 3.7 million copies, and an impressive if not Potter-level 1.3 million were sold in the first twenty-four hours.

For the purposes of discussing plot and theme and so forth, I’m going to conflate the novels and their faithful film adaptations, the latter more like brand extensions than movies with inner lives of their own. The premise of the first Twilight installment is fairly simple (and the core dynamic holds steady through most of the series, even as the plotting can feel simultaneously convoluted and static). Isabella Swan, who goes by Bella, has moved from Arizona, where she was living with her mother, to a small town called Forks (a real place) in the rainiest, woodsiest, gloomiest corner of Washington State. Bella’s dad is the taciturn local police chief; they get along perfectly well but aren’t close, so Bella is essentially on her own, which, along with the spooky-forest setting, lends the story a fairy-tale undercurrent. She tries to put a good face on things, but she doesn’t like the weather and she’s bored by small-town life.

The only thing at her new high school holding any interest is the spectral presence of the Cullens, five “chalky pale … inhumanly beautiful” teenagers, the adoptive children of a local couple. Aloof like any worthy cool kids, they keep to themselves in the cafeteria. Bella and Edward, the most inhumanly beautiful Cullen of all, meet-cute-ish when she’s forced to sit next to him in biology lab and he seems agitated by her presence, even repulsed. Circumstances and the push-pull of romance novel conventions keep throwing them together. As Bella narrates one encounter (in a representative sampling of Meyer’s prose):

We were under the shelter of the cafeteria roof now, so I could more easily look at his face. Which certainly didn’t help my clarity of thought.

“It would be more … prudent for you not to be my friend,” he explained. “But I’m tired of trying to stay away from you, Bella.” His eyes were gloriously intense as he uttered that last sentence, his voice smoldering. I couldn’t remember how to breathe.

Once she regains neuromotor function, Bella takes to the Internet for some cursory sleuthing and figures out that he is a vampire, as are the rest of the Cullen family. (More formally, a “coven.”) When she confronts him — the meadow scene of Meyer’s initial dream — he confesses both his true nature and his own desperate love for her. But here is the catch: not only is Edward a 103-year-old immortal in the body of a seventeen-year-old hottie, but if he gives in to his attraction for Bella, his passion will almost surely get the better of him and he will drink her blood and turn her into a vampire herself. That’s why he was acting so weird in biology lab! He was fighting the urge to chomp down on her neck!

“I’ve never wanted a human’s blood so much in my life. It’s you. It’s your scent,” the movie Edward tells Bella (rewriting dialogue from the book). “You’re like a drug to me. You’re my own personal brand of heroin.” But the Cullens are good vampires in that they’ve forsaken human blood and only dine on forest animals. Edward likens their self-imposed dietary restrictions to giving up meat for tofu: you’re less satisfied but you get used to it.

This, then, is the crux of Twilight: Bella loves Edward and wants to have sex with him; he loves her and wants to have sex, too, but must restrain himself for her own good. Even were he able to control his thirst for her blood during lovemaking, we are told that his superhuman vampire strength might literally break her. Fortunately, because he became a vampire back in 1919 (his vampire “father” saved him from succumbing to Spanish flu by making him immortal), Edward is an old-fashioned lad and believes in waiting until marriage.

The books and films thus create a kind of fantasy safe space where sexual desire, especially female desire, is acknowledged and even tacitly celebrated, yet also held in check for the good of all — with the twist that here it’s the boy who hits the brakes, acting as guardian of virtue, rather than, per usual, the girl. In a bedroom scene in the film, Edward breaks off from an increasingly passionate kiss by hurling himself across the room (a vampiric skill), recoiling from further intimacy “like a distraught Victorian,” as the New York Times critic Manohla Dargis put it.

“I’m stronger than I thought,” Edward reassures himself.

“I wish I could say the same,” Bella says with a sigh, looking thoroughly dazed.

“I can’t ever lose control with you,” he vows.

Cue audience shivers. They then lie together chastely in bed, she falling asleep while he, who never sleeps, watches over her. In fact, so protective is Edward that he drives a Volvo station wagon, one of the safest if least-sexy cars on the market. Earlier generations of teen movie heroes, like James Dean’s Jim Stark from Rebel Without a Cause, or Matthew McConaughey’s Wooderson from Dazed and Confused, would gag.

Meyer added some evil vampires to the mix for menace and invented a chiseled teenage werewolf to serve as an alternate love interest–cum–third wheel (sparking the Team Edward vs. Team Jacob face-offs that divided a generation’s worth of slumber parties). But it’s the sexual tension between Bella and Edward, the longing and self-denial, which drives the series. You can understand the appeal of this updated lemonade-on-the-veranda courtship to an oversexed/undersexed generation, and not just girls. A boy who told Nancy Jo Sales — the author of the 2016 book American Girls: Social Media and the Secret Lives of Teenagers, which catalogued the evolving sexual norms of kids — that he owned “a scoring average higher than Kobe Bryant’s” also confessed that he longed to live “when you had to go knock on the door and ask the dad for permission.” Which at one point Edward more or less does, formally introducing himself to Bella’s father.

“Like American culture itself, Twilight is both lascivious and chaste,” the critic and journalist Sarah Seltzer has observed. Meyer found a way to transform the impulse behind virginity pledges, purity balls, and abstinence-only sex education into something erotic and dangerous. The critic Christine Seifert, writing in Bitch magazine, memorably labeled Twilight “abstinence porn.” It’s instructive, too, to look at Twilight in the tradition of teen horror, which has traditionally been awash in conflicted notions about sex. Movies from I Was a Teenage Werewolf to Carrie treat the teenage body as an object of fear and disgust, while slasher films like the Friday the 13th and Nightmare on Elm Street series delight in the bloody punishment of sexually active teens, even turn it into sport. By those standards, the Twilight novels and films are sex positive.

Vampire stories have their own sexual undercurrents — or not really “under” since the lust for blood and the biting of necks and attendant exchange of bodily fluids are but the most diaphanous of metaphors, barely a negligee. The vampire, most often a he, is traditionally a libertine and seducer. Meyer’s stroke of genius was to make her lead vampire an avatar of self-sacrifice and bodily temperance. But at the same time, Edward is entirely red-blooded, as it were. He has all the manners and nobility (and alabaster pall) of Ashley Wilkes, but with Rhett Butler’s pheromones and knowing smiles. In fact, he’s pretty much the perfect boyfriend, aside from being undead and subsisting on forest animals.

However strategic Edward’s restraint was on Meyer’s part, it was also informed by her devout Mormon faith. “When my editor wanted pre- marital sex in my story, I explained that I won’t write that,” she told an interviewer.

Marital sex was not in her authorial wheelhouse, either: Bella and Edward finally tie the knot in Breaking Dawn, but Meyer skips over the consummation with a discreet line break. This disappointed her randier readers, who compensated by writing their own explicit fan fiction, much of it focused on Bella and Edward’s honeymoon on a secluded tropical island off the coast of Brazil. But for other fans, any sex, even wedded, even discreet and off-page, was divisive. Within days of Breaking Dawn’s publication, Goodreads was filled with complaints that the book was “anticlimactic” and/or “gross.” On a Twilight message board, someone complained, “The sweep and scope of a grand love affair was gone. The brilliantly innocent eroticism that took our breath away was also gone.”

I can’t venture an opinion pro or con on Bella and Edward’s lovemaking, but I very much like the oxymoron “innocent eroticism.” It captures Meyer’s achievement.

*****

Meyer’s books had first been optioned for film by Paramount, which misunderstood their appeal, reportedly commissioning an action-oriented screenplay that diverged from the novel, recasting Bella as a track star, and climaxing with a Jet Ski chase. Perhaps the impulse was to broaden the story’s appeal by getting Bella out of Pacific Northwest wear and into a bathing suit? The project quickly went into turnaround.

Summit Entertainment picked it up. Sales of the books hadn’t yet exploded, so initial expectations for the movies were allegedly modest — which, according to Catherine Hardwicke, who directed Twilight, is why she got the job: “Why do you think they hired a female director? If they thought it was going to be a big blockbuster, they wouldn’t have ever hired me, because no woman had ever been hired to do something in the blockbuster category.” All those passionate online fans, the studio worried, “could just be 400 girls in Salt Lake City blogging about it,” in Hardwicke’s words. Summit viewed Twilight as akin to Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, another film based on a YA novel with a primarily female fan base that had been cheap to make and had returned a decent profit for Warner Bros. in 2005 with a global box office of $42 million.

Hardwicke’s calling card as a director was Thirteen, her first film, released in 2003, a teens-today shocker set in L.A. that starred a fourteen-year-old Evan Rachel Wood, in her first major film role. When the director read Meyer’s novel, she found something she could connect to: “I wondered if that intoxicating first love could be put onscreen — as a filmmaker could I create that ‘drug’ that she created, we’ve all felt, or at least most people at a certain age have felt. I saw that as an extreme challenge.”

To that end, she discarded the script she had inherited from Paramount. Hardwicke realized that what makes Bella such an appealing heroine is not that she’s a track star or aces on a Jet Ski, but rather that she’s average — in the novel Meyer has the character describe herself as “absolutely ordinary.” She is perhaps a little smarter and more observant than her peers, but also self-conscious, unathletic to the point of being clumsy, lacking in any particular passions (aside from, eventually, Edward). The new girl in town, she is something of a loner, aloof from friend-group drama. Perhaps most importantly, she is rigorously unglamorous, having zero interest in clothes, makeup, shopping — which must have further endeared her to a generation of girls exhausted by posing for selfies.

Kristen Stewart is, of course, far from ordinary — but movies need movie stars, and her recessive charisma works for Bella. A meme that circulated about Stewart in the Twilight films, “FIVE MOVIES, ONE EXPRESSION,” is funny but not, I think, fair. She can hold a screen without doing a lot, and her default sullenness helps an ultimately ridiculous story keep one foot sort of on the ground. It’s an effective and watchable performance, with perhaps a less emotive echo of Molly Ringwald in her John Hughes movies.

Stewart was seventeen when Twilight was in production. The male lead, Robert Pattinson, was a twenty-two-year-old Londoner who had dabbled in modeling and singer-songwriting before turning to acting. He was one of three possible Edwards who Hardwicke brought to her house in Venice to read with Stewart. “When Rob and Kristen met, all of us could tell there was a very strong chemistry there,” the director recalled. “You know, just electricity. It was very intense.” She had the two actors perform the I-must-control-myself-with-you kissing scene “about three times,” on her own bed. More sparks. “When everyone was gone,” Hardwicke said, “Kristen was like, ‘You have to cast Rob.’”

Pattinson was offered the role the next day, buoyed not just by his chemistry with Stewart but by Summit’s modest expectations for the film, a blessing that allowed Hardwicke to cast two more-or-less unknowns “rather than a famous movie star from the Disney Channel or whatever,” as she put it. In her mind, she was directing another indie movie, only with a slightly bigger budget and some special effects. For the most part the studio agreed and left her alone. “We just made it, and really in a personal way,” she said later.

Meyer’s fans weren’t as laissez-faire as Summit, scrutinizing the production’s every move, not least the casting. Stewart was generally received favorably. Pattinson wasn’t so lucky. Though to anyone’s eyes he was a perfectly attractive young man, he wasn’t in tip-top physical shape and was prone, moreover, to feckless grooming and dishabille. (According to Hardwicke, he had shown up for his audition with “wacky bangs” and a “messy” shirt.) He was not, in other words, inhumanly beautiful.

“When Rob was announced, people had a meltdown on the internet,” Hardwicke recalled. “People said horrible things. There were a few pictures of him by the paparazzi that were in London, walking out of a club, not having shaved, looking like a slob. I said to Rob, ‘As soon as we get your look down and your photos [in character] out, I know you’re going to be good. You just have to have faith. This happens to a lot of actors.’ One day he came to me and said, ‘I got this email forwarded to me about how revolting I am.’ I said, ‘Rob, you cannot read these things. Don’t torture yourself.’ And he said, ‘I didn’t. My mother forwarded me that.’”

Fans grew less restive after Meyer publicly endorsed Pattinson. But there was another online eruption when the two leads were featured in an embrace on an Entertainment Weekly cover five months before the movie’s release. With Stewart’s shoulders bared and Pattinson wearing what looked like an unbuttoned pirate shirt, the image suggested a swash-buckling romance more than the paranormal sort. Of even greater offense was Pattinson’s fluffy, Kennedy-esque haircut and — worse still — a patch of fur visible on his chest. “Horrible,” wrote one message board dissenter. “He looks like a hairy powdered donut.”

Earlier teen movie stars like Mickey Rooney, James Dean, and Molly Ringwald had committed, even lunatic fans, but they didn’t have to deal with the blast furnace attention of contemporary “fandoms,” in which collective passions, enabled and unleashed by social media, foster a sense of ownership and entitlement. Stewart and Pattinson were among the first. (Facebook was four years old in 2008, when Twilight premiered, Twitter was two, and five-year-old MySpace was only just beginning its decline.)

Pattinson’s look as Edward was eventually redeemed by a floppy pompadour — James Dean by way of a boy band — and his (and his trainer’s) achievement of a chiseled, depilated, marble-smooth torso. To say that the fans ultimately took to him would be an understatement. His Edward works wonders on Stewart’s Bella, who spends much of the first movie staring at him, lips apart, across the high school lunchroom and parking lot. He reciprocates: Twilight is a movie built on staring, which is appropriate, I suppose, for a film about sublimated desire. Stewart gives the more naturalistic performance. Pattinson is more mannered, his sangfroid studied but effective; at times he seems to be channeling Luke Perry’s Dylan McKay from Beverly Hills 90210, yet another in the long line of sensitive, brooding, misunderstood pretty boys descended from Dean’s Jim Stark — which suggests that 103-year-old Edward has at least kept up with teen culture. A different movie might have profitably explored the existential dilemma of having to repeat high school across nine decades — how many times has Edward had to read The Grapes of Wrath or learn to solve quadratic equations? — but that might have struck too literal a note for a heady paranormal romance.

Whatever the mix of chemistry, skill, and attitude, the leads make the romance work onscreen — they also became a couple in real life for a year or two — which is of course essential to making the movie work as a whole, and even more so than with most love stories; given that this one has vampires, something has to be believable. The production’s modest scale and Hardwicke’s indie-inflected direction help, too; you feel like she’s capturing scenes on the fly, which keeps even the supernatural business tethered to life on earth (a few clumsy special effects aside). The movie, especially in its early scenes, almost convinces you it’s a story about two normal kids, one of whom might be a vampire, but don’t judge.

The tone shifts, though, becoming myopic and even a little queasy once the film leaves high school behind and heads deeper into the forest, literally and figuratively, a shift that mimics the swoony, woozy, consumptive rush of first love — just what Hardwicke intended to capture. I don’t want to overstate the case for Twilight as a film, but you have to admire the skill of everyone involved in creating such an effective picture given the limitations — a significant one being that the screenplay gives Edward no real reason for falling in love with Bella beyond her scent, though in fairness, many adolescent romances have been born of less, even if those relationships tend to be measured in months or weeks, rather than eternity.

Twilight grossed $69.6 million on its opening week in North America, then a record for a film directed by a woman. Hardwicke’s reward was getting booted from the sequel, ostensibly because of — the usual — creative differences, which may even have been the truth. But “one insider” leaked to Nikki Finke (the caustic and relentless showbiz journalist whose website, Deadline Hollywood Daily, was a source of terror and Schadenfreude in the entertainment industry across the 2000s and early 2010s) that Hardwicke was “difficult” and “irrational,” which, the source admitted, “doesn’t mean anything when you’re talking about a filmmaker because they all are, but still …”

That “but still” does a lot of work here, more or less proving Hardwicke’s assertion, once Twilight had proven itself, that Hollywood would not trust women with big franchises.

Summit’s choice to direct New Moon was Chris Weitz, who, like Hardwicke, had prior teen movie credibility, though not of the sort most Twihards, as fans labeled themselves, approved of. “I understand that,” Weitz said of the enusing outrage. “I directed American Pie. I would be worried too.” And, well, yes: it was an alienating move, inviting the male director of a comedy about having sex to helm a female-centered romance about not having sex. Weitz did come with a prior franchise movie on his résumé, having directed a 2007 adaptation of the first novel in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy, The Golden Compass. Alas, it had flopped, stifling planned follow-ups. But still … he was Summit’s choice.

To my mind, the most interesting thing about New Moon is its opening, in which Bella dreams that Edward is now with some wizened old lady who turns out to be … Bella! This nightmare has been brought on by the fact that she is about to turn eighteen while he, cursed or blessed, will remain an eternal seventeen. “You’re not going to want me when I look like a grandma,” she tells him. Given teenage revulsion if not denial at the thought of aging, this might be the scariest moment in the entire series.

Adapted from Hollywood High: A Totally Epic, Way Opinionated History of Teen Movies by Bruce Handy. Copyright © 2025 by Bruce Handy. Reprinted by permission of Avid Reader Press, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC.