How Martin Scorsese’s films record modern American cinema’s savage beauty

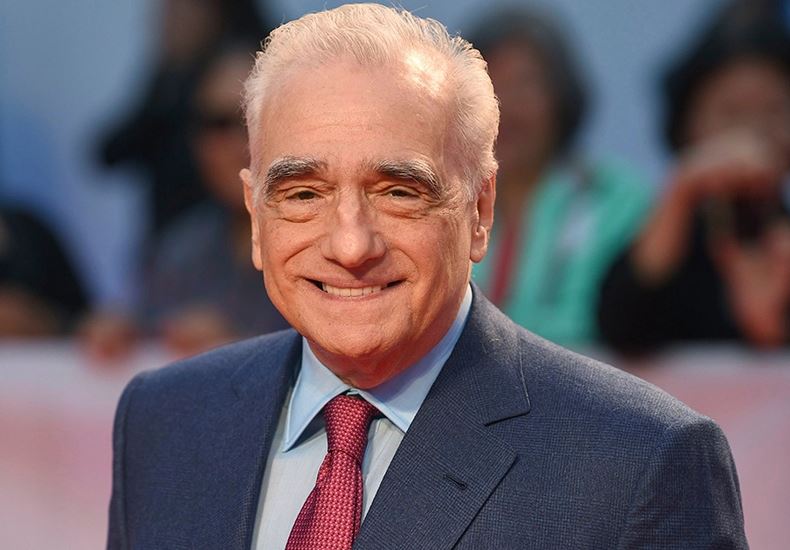

“The principal anguish and the source of all my joys and sorrows from my youth onward has been the incessant, merciless battle between the spirit and the flesh,” writes Nikos Kazantzakis in the opening pages of his novel, ‘The Last Temptation of Christ’ (1952), which is the basis of Martin Scorsese’s 1988 film of the same name. Having espoused and then rejected many beliefs, Kazantzakis, a stalwart of Modern Greek literature, continued to seek closer relationship with God, but remained torn between faith, art and the temptations of living in the modern world. His evocation of his conflicted life in ‘The Last Temptation of Christ’ offers an insight into the films by Scorsese, one of America’s greatest cinematic storytellers, who turned 80 on November 17.

In film after film, the master of neo-noir, with a cult following around the globe, courageously explores — across his 25 films and 16 documentaries — how ‘the passions that bind us together can also destroy us’. His films laced with the lure of violence crime and greed — ‘Mean Streets’ (1973), ‘Taxi Driver’ (1976), ‘Raging Bull’ (1980), ‘Goodfellas’ (1990) and ‘The Wolf of Wall Street’ (2013) — are signposts to a style of filmmaking that the auteur has made joyously his own: these films betray the ‘savage beauty of great intensity and truth.’ They are also, in popular imagination, the receptacle of all the Scorsese trademarks: long tracking shots, freeze frames, split-diopter shots, slow-motion, crime, corruption, bad blood, violence.

The master auteur

Scorsese has rightfully claimed the mantle of Stanley Kubrick (1928-1999), a true master of modern cinema, whose thirteen feature films and three short documentaries are intellectually rigorous, narratively challenging and technologically trailblazing; Kubrick and Federico Fellini (1920-1993) have inspired the Italian-American filmmaker the most. In a career spanning five-and-a-half decades, Maty (as Martin Scorsese is known in the circle of his admirers) has directed a string of films steeped in the noirish element of gangster violence: ‘Mean Streets,’ ‘Taxi Driver’, ‘Goodfellas’, and ‘Casino’ (1995).

Also read: Kantara makers vs Thaikuddam Bridge: Kerala band to file another case

These films are classic Scorsese since they foreground dramatic themes with which he has been preoccupied: violence, corruption, and moral decay. However, with their tremendous allure, these films have also led to Scorsese being cast in a stereotypical image as a filmmaker who revels in savagery on celluloid, in the same way that Billy Wilder is seen as primarily a maker of screwball comedies or Woody Allen as the maker of existentialist comedy/drama. However, as Mark T. Conard writes in the Introduction to ‘The Philosophy of Martin Scorsese’ (2007), a volume of essays, this stereotyping of Scorsese is unjustified since his films encircle a wide range of topics and themes.

Wilder was pigeonholed because of his two wildly famous films: ‘The Seven Year Itch’ (1955) and ‘Some Like It Hot’ (1959). Similarly, Allen was put in a bracket because of ‘Annie Hall’ (1977) and ‘Manhattan’ (1979). But why should we forget that Wilder also directed ‘Double Indemnity’ (1944) and ‘Sunset Boulevard’ (1950)? In the same way, Allen’s oeuvre also includes ‘Interiors’ (1978), ‘Another Woman’ (1988), and ‘Match Point’ (2005). Scorsese, on his part, has also made ‘Kundun’ (1997) — the story of the early life of the 14th and current Dalai Lama — ‘The Last Temptation of Christ’ and The Aviator (2004). He draws on the social mores in 19th-century New York in ‘The Age of Innocence’ (1993), pool hustling in ‘The Color of Money’ (1986), and the boxer Jake La Motta in ‘Raging Bull’ (1980). Besides narrative feature films, Scorsese has also made documentaries — ‘The Last Waltz’ (1978) and ‘No Direction Home: Bob Dylan’ (2005) — as well as music videos like ‘Michael Jackson’s Bad’ (1987).

The Beginning

Scorsese made his feature film debut with ‘Who’s That Knocking at My Door’, a black-and-white personal film, in 1967. It marked the student of film history’s earnest attempt to arrive at a visual vocabulary, his effort to learn about the art of storytelling, structure, time, and place. At this juncture, Scorsese did not have the cinematic syntax and invention of a Jean-Luc Godard or a Bernardo Bertolucci to express the inner feelings of a ‘personal filmmaker’.

His bids to learn the craft of a feature film form — use of camera, mise-en-scene, staging and performances — is also evident in the crime drama ‘Boxcar Bertha’ (1972). Though his second feature film was a significant improvement upon the first, he couldn’t lend the film technical finesse and narrative refinement. Scorsese was, however, able to capture the atmosphere of the story revolving around those living on the fringe of society, and bring the characters to life, layering the narrative with rich subtext.

Inspired by Italian neo-realism and John Cassavetes’s ‘Shadows’ (1959), American independent drama film about race relations during the Beat Generation years in New York City, ‘Mean Streets’ effectively propelled Scorsese’s career as a major filmmaker. Above all, it shattered decades of stereotyping of Italian-Americans in film and television and became the first American film to showcase Italian-Americans as they really lived. For several decades, Hollywood had perpetuated the image of Italian-Americans as garlic-eating and hot-headed, but lovable and passionate people either in middle-class professions (barbers, shoemakers, fruit and vegetable vendors) or as evil but charismatic members of organized crime known as the Mafia.

Also read: Cracked mirror: The cinema of the infinitely resilient women of Iran

‘Mean Streets’ begins with a voice-over: “You don’t make up for your sins in the church — you do it in the streets — you do it at home — the rest is bullshit and you know it.” Suddenly, protagonist Charlie Cappa (Harvey Keitel) wakes up. The connection between Scorsese and Charlie is established immediately. Scorsese’ family is embodied in the film’s principal character: Charles is his father’s first name and Cappa his mother’s maiden name. Scorsese’s voice becomes Charlie’s conscience.

Morally complicated characters

Some of Scorsese’s films portray lives tinged with crime and violence and have come to be seen as the bedrock of his career. However, it would be reductive to claim that he has limited himself to a particular theme. What we can, however, say is that there are threads running throughout his films that give us a sense of some of the ideas that he has embraced as a filmmaker. The conflict between faith and art is one such idea.

Scorsese’s morally complicated characters, including criminals and murderers, show the frailty of human beings. A quest for identity is central to these characters and it brings them closer to the temptations of violence, lust, and greed. He does not want us to celebrate the hedonistic pursuits and insatiable greed of Jordan Belfort (Leonardo DiCaprio) in ‘The Wolf of Wall Street’ (2014) or the involvement of Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) in the Lufthansa heist in ‘GoodFellas (1990). But the director insists that these deeds are worthy, to be explored and dramatized. “Very often the people I portray can’t help but be in that way of life. . . . Yes, they’re bad, they’re doing bad things, and we condemn those aspects of them—but they’re also human beings. I want to push the audiences’ emotional empathy,” the filmmaker, who has been criticised for the depiction of violence in his films, said in an interview once.

Also read: What makes Dwayne Johnson Hollywood’s strangest success-story

The Academy award-winning director, producer and screenwriter’s last crime saga, ‘Irishman’, sprawling across more than a century of American history, was a Netflix release in 2019. In a review in The New Yorker, Richard Brody termed the film as a dark allegory of a realist reading of American politics and society: “The Irishman is a socio-political horror story that views much of modern American history as a continuous crime in motion, in which every level of society — from domestic life through local business through big business through national and international politics — is poisoned by graft and bribery, shady deals and dirty money, threats of violence and its gruesome enactment, and the hard-baked impunity that keeps the entire system running.”

Idea of filmmaking

For Scorsese, filmmaking, though personal, is not an individual art. Collaboration has been a key force in his career as evident in his series of films with DiCaprio and Robert De Niro. He continues to be in love with the idea of good old cinema. In 2019, in an op-ed in The New York Times, he argued that Marvel movies are not cinema: “I suppose we also have to refine our notions of what cinema is and what it isn’t. Federico Fellini is a good place to start. You can say a lot of things about Fellini’s movies, but here’s one thing that is incontestable: they are cinema. Fellini’s work goes a long way toward defining the art form.”

A host of factors has shaped Scorsese’s distinct style of filmmaking. Scorsese was brought up in New York’s Little Italy. In his films, he keeps returning to the crime-laden landscape of his native city during the 1970s as a metaphor for the world at large. Scorsese’s struggles with asthma as a child — it steered him away from the passion of playing sports — and his early desire to enter the priesthood have also shaped his sensibilities as a filmmaker preoccupied with the constructs of community, religion and violence.

Scorsese’s forthcoming film, ‘Killers of the Flower Moon’, based on American author David Grann’s broadly lauded bestselling book of the same name, releases in May 2023. Set in the 1920s Oklahoma, it will trace the serial murder of members of the oil-wealthy Osage Nation, a string of brutal crimes that came to be known as the Reign of Terror. The film marks the sixth collaboration between Scorsese and DiCaprio; with De Niro, it will be his 10th partnership.

His gangster films have earned him fame, and notoriety. But the trajectory of Scorsese as a filmmaker has been marked by constant evolution. If he made ‘Mean Streets’ and ‘Goodfellas,’ he has also directed a visually and narratively stunning film like ‘The Age of Innocence’ (1993), the tale of nineteenth-century New York high society, and ‘After Hours’ (1985), a comedy that explores how vulnerable we are to the appearance of absurdity.